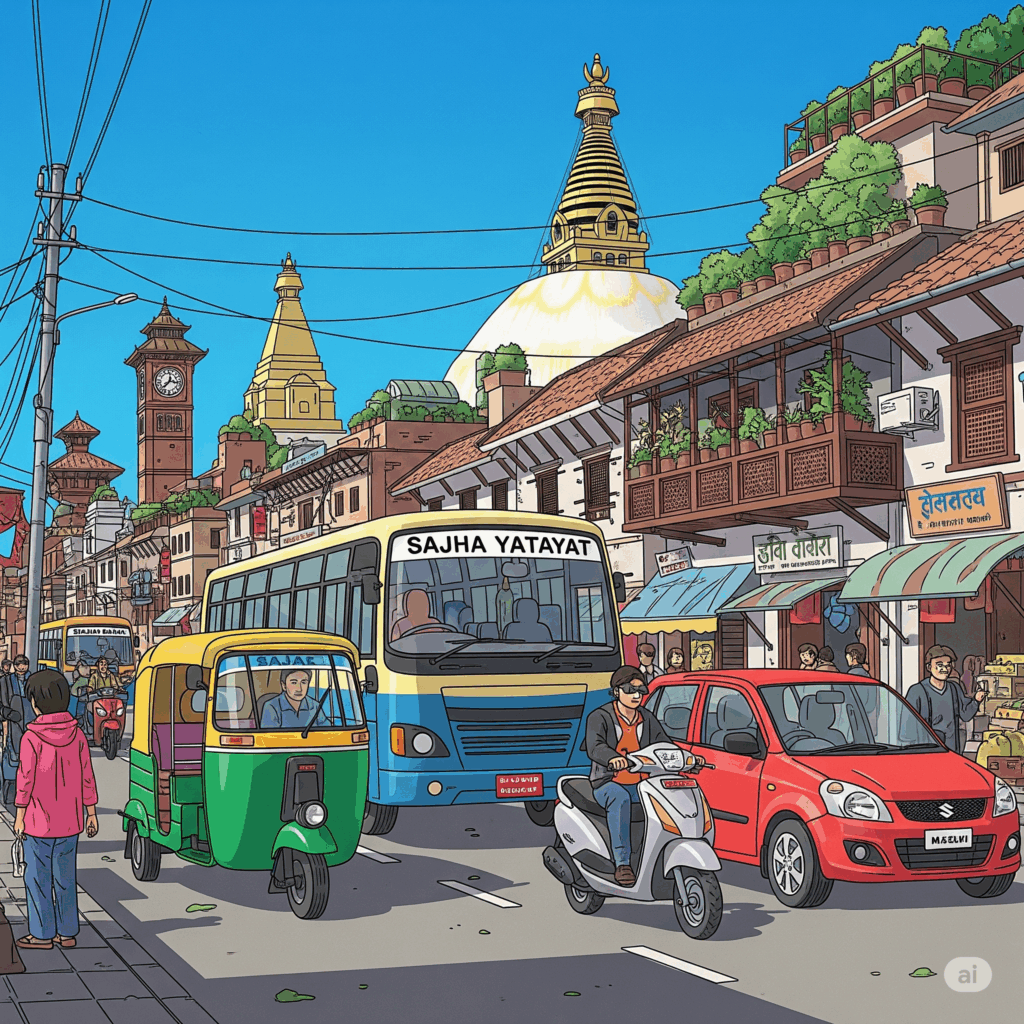

Nepal’s journey with electric vehicles (EVs) is a tale of innovation, environmental necessity, and resilience, beginning with the pioneering efforts of Peter Moulton and the Global Resources Institute (GRI) in the early 1990s. What started as a modest experiment with the Safa Tempo has evolved into a broader movement, positioning Nepal as an unexpected contender in the global shift toward sustainable transportation. This article traces the history of EVs in Nepal, from their humble origins to the present day, drawing on insights from related articles and contemporary developments.

The Birth of Safa Tempos: A Vision Takes Root

The story of EVs in Nepal begins in 1990, when Peter Moulton, alongside his wife Marilyn Cohen, spearheaded an initiative under the Kathmandu-Eugene City Committee to address Kathmandu’s worsening air pollution. As detailed in Makeshift Mobility, Moulton and Cohen, through the Global Resources Institute, proposed converting the city’s polluting diesel-powered Vikram Tempos—three-wheelers notorious for belching black smoke—into electric alternatives. With funding from USAID, GRI developed the Safa Tempo, meaning “clean three-wheeler” in Nepali, using off-the-shelf parts like deep-cycle lead-acid batteries, similar to those in golf carts.

The Safa Tempo was a practical solution tailored to Kathmandu’s slow traffic and short transit routes. After a successful six-month demonstration in 1993, ferrying over 200,000 passengers across 175,000 kilometers, the project caught the attention of local entrepreneurs. As noted in CityLab, the technology was handed over to the Nepal Electric Vehicle Industry (NEVI), founded by mechanical engineer Bijay Man Sherchan. Sherchan envisioned Kathmandu as a “Shangri-La for electric vehicles,” a dream articulated in his 1997 op-ed. By 2000, over 600 Safa Tempos roamed the city, forming the world’s largest fleet of battery-powered public transport vehicles at the time.

This early success was remarkable for a nation grappling with poverty and limited infrastructure. Bloomberg highlights how Nepal briefly led the zero-emission public transportation revolution, with Safa Tempos—many driven by women—offering a quieter, cleaner alternative to the chaotic buses and microbuses clogging Kathmandu’s streets.

Early Milestones: Trolleybuses and Pre-Safa Efforts

While the Safa Tempo marked a turning point, Nepal’s EV history predates Moulton’s initiative. In 1975, the Chinese government gifted Nepal a trolleybus system, spanning 13 kilometers from Tripureshwor in Kathmandu to Surya Binayak in Bhaktapur, as documented in Nepal Economic Forum. This state-owned service, powered by Nepal’s abundant hydropower, was an early nod to electric mobility but faltered by 2009 due to poor maintenance and financial woes.

The 1989 fuel crisis, triggered by an Indian trade embargo, further spurred interest in EVs. The Electric Vehicle Development Group converted a Volkswagen into a battery-powered prototype in 1992, laying groundwork for the Safa Tempo project, according to Motion Digest. These efforts underscored Nepal’s recurring need for alternatives to imported fossil fuels, a theme that would resurface with the Safa Tempo’s rise.

The Golden Era and Decline of Safa Tempos

The late 1990s and early 2000s were a golden era for Safa Tempos. Supported by government policies banning diesel three-wheelers and incentives like tax exemptions, the fleet grew to over 710 units, serving 1.5 million commuters daily across 14 routes, per Setoghar. The Danish agency DANIDA bolstered this growth by funding training for drivers—nearly half of whom were women—and establishing charging stations.

However, this momentum stalled at the turn of the millennium. Green Car Reports explains that the end of tariff exemptions for Vikram Tempo owners in 2000 prompted a shift to larger, fossil-fuel-powered Toyota microbuses. Local manufacturing of Safa Tempos ceased, unable to compete with entrenched transit operators and inconsistent government support. By the early 2000s, the dream of an EV-dominated Kathmandu faded, though the aging fleet persisted, operated by small-scale entrepreneurs.

Revival and Modern Expansion

The Safa Tempo’s decline did not mark the end of EVs in Nepal. The late 2000s saw a resurgence, driven by private-sector innovation and renewed environmental urgency. Indian manufacturer Mahindra introduced the Reva, while China’s BYD debuted the e6—initially for presidential use—in the early 2010s, as noted in Nepal Economic Forum. The end of load-shedding in 2018, thanks to hydropower expansion, further catalyzed EV adoption.

By the 2020s, Nepal’s EV market exploded. Customs data from The Kathmandu Post shows a 149% surge in EV imports in the fiscal year ending mid-July 2024, totaling 11,701 units worth Rs29.48 billion. Brands like BYD, Tata, Hyundai, and MG now dominate, supported by tax breaks (25-90% import duties versus 276-329% for fossil fuel vehicles) and bank financing covering up to 90% of costs. The government’s Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) targets—25% of private and 20% of public four-wheelers electric by 2025—reflect this ambition.

Challenges and the Road Ahead

Despite this progress, challenges persist. Charging infrastructure remains urban-centric, with over 100 stations but few in rural areas, per Dialogue Earth. Battery replacement costs and e-waste management are unresolved issues, as highlighted by Nepal Economic Forum. Moreover, the dominance of Chinese brands—69% of imports in 2024—raises concerns about reliability and after-sales support, with fears of companies exiting and “ghosting” customers, a risk flagged by Fiscal Nepal.

Yet, Nepal’s EV story is far from over. With hydropower fueling its grid and a legacy of innovation sparked by Peter Moulton’s Safa Tempos, the nation stands at a crossroads. As Aloi suggests, reviving local manufacturing—perhaps even batteries—could reclaim Nepal’s early promise. The Safa Tempo, once a global pioneer, remains a symbol of what’s possible when necessity meets ingenuity.

Nepal’s EV history, from Moulton’s vision to today’s bustling market, is a testament to its potential as a leader in sustainable mobility. The question now is whether it can build on this legacy to create a truly electric future.